Getty Images

Over the past year, a flurry of destructive Wiper malware has appeared from no less than nine families. In the past week, researchers have cataloged at least two more, both with advanced codebases designed to deal maximum damage.

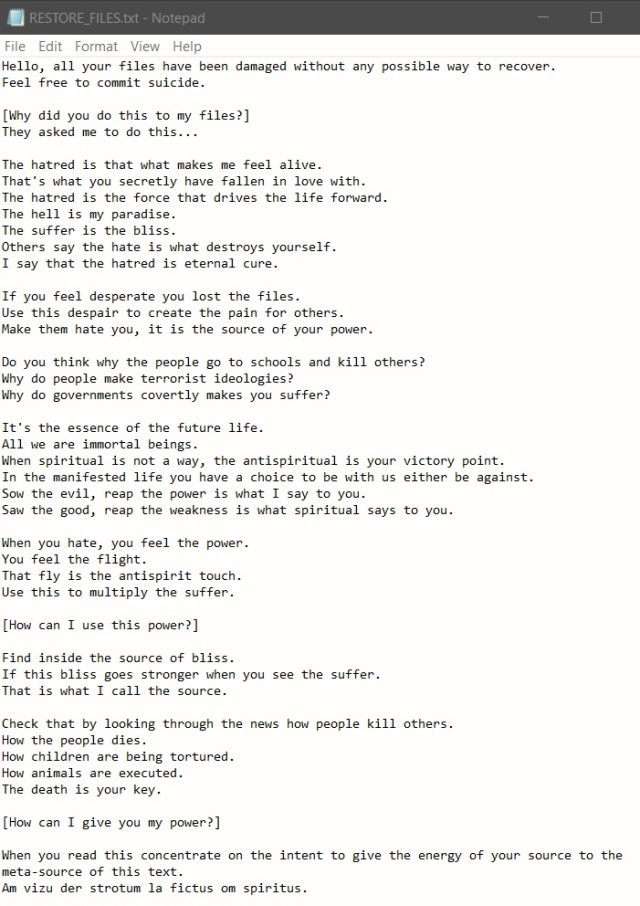

On Monday, researchers at Check Point Research released details of Azov, a never-before-seen piece of malware that the company described as an “effective, fast and sadly unrecoverable data eraser.” Files are erased in 666-byte blocks by overwriting them with random data, leaving an identically sized block intact, and so on. Malware uses uninitialized local variable char buffer[666].

Script kiddies need not be applied

After permanently destroying data on infected machines, Azov displays a note written in the style of a ransomware ad. The note echoes the Kremlin’s talking points on Russia’s war against Ukraine, including the threat of nuclear strikes. The note of one of the two samples recovered by Check Point falsely attributes the words to a well-known Polish malware analyst.

Despite the initial appearance of a business from young developers, Azov is by no means simple. It is a computer virus in its original definition, meaning that it modifies files, in this case by adding polymorphic code to 64-bit backdoor executables, that attack the infected system. It’s also written entirely in assembly, a low-level language that’s extremely painstaking to use but also makes malware more effective at the backdooring process. In addition to the polymorphic code, Azov uses other techniques to make it more difficult for researchers to detect and analyze.

“Although the Azov sample was considered skidware when first encountered (probably due to the oddly formed ransom note), when further analyzed one finds very advanced techniques: hand-crafted assembly, injecting payloads into executables to execute backdoors and several anti-analysis tricks usually reserved for security textbooks or high-profile branded cybercrime tools,” wrote Check Point researcher Jiri Vinopal. “Azov ransomware should certainly give the typical reverse engineer a harder time than the average malware.”

A logic bomb embedded in the code detonates Azove at a predetermined time. Once triggered, the logic bomb iterates over all file directories and runs the cleanup routine on each of them, except for specific hard-coded system paths and file extensions. As of last month, more than 17,000 backdoored executables have been submitted to VirusTotal, indicating that the malware has spread widely.

On Wednesday, researchers at security firm ESET revealed yet another never-before-seen windshield wiper they’ve called Fantasy, along with a side-move and run tool called Sandals. The malware was spread using a supply chain attack that abused the infrastructure of an Israeli firm that develops software for use in the diamond industry. Over a 150-minute period, Fantasy and Sandals spread to the software maker’s customers engaged in human resources, IT support services, and diamond wholesaling. The targets were located in South Africa, Israel and Hong Kong.

Fantasy borrows its code heavily from Apostle, malware that initially posed as ransomware before revealing itself as a windshield wiper. Apostle has been linked to Agrius, an Iranian threat actor operating out of the Middle East. Code reuse has led ESET to place Fantasy and Sandals in the same group.